Body and Soul

The Understanding of Life and Death in Antiquity

The greatest riddle of life is death. What happens when someone dies? Why is it that someone who was, a few minutes beforehand, quite active and even talkative, suddenly inert and silent?

In antiquity, the explanation was that a living person was made up of two parts - body and soul. The body was what we still think a body to be, a physical assemblage of flesh and blood. The soul was what acted to animate the body, to breathe life and movement and sensation into what was otherwise inert matter. At death, this vitalizing spirit left the body, which, with the spark of vitality vanished, decayed and rotted.

|

| The soul, as a human-headed hawk, visits the mummified body |

The soul came to be regarded as immaterial, or near-immaterial, because nobody saw the soul leave the body. A human body weighed as much after death as it did before death, and so what had left had to be insubstantial, yet real.

This explanation of death had logical consequences. Since the soul was what animated the body, it could not itself be mortal, because it was itself the essence and principle of life. It was not in the nature of this life-essence to die. When body and soul parted company, the body decayed into dust, but the immortal soul continued in existence.

Equally, at birth, a new creature was vitalized by being joined with a soul. In one account, found in the Western world, each new individual body that appeared came with a new soul. In other accounts, predominantly found in the Eastern world, each new living being was assigned a pre-existing immortal soul, which left it at death. Thus, in this latter account, a more or less fixed number of souls moved from body to body, from one generation to the next. A soul might at one time animate a man, but it could next animate a bird or a horse or a tree. There was a certain economy to this account, for if each new life entailed the creation of a new immortal soul, then the number of souls had to be increasing arithmetically with time.

In the Western account, if body and soul were separated at death, then there was nothing, in principle, to stop them being re-united, and for the dead to come back to life. In order to facilitate this possibility, it came to be felt that the bodies of the dead should be preserved as best they possibly could. Burial and mummification served to maintain the body for this future event. According to the Eastern account, however, since the soul moved from one incarnation to another, there was no need to preserve a body for future re-union with its vitalizing soul: it could be burned, and the ashes dispersed.

The different account of the soul in East and West made for a different scheme of history. In the East, the animating souls moved interminably from one body to the next, on the wheel of Samsara, endlessly being reborn. Thus the Eastern account of history is one of equilibrium, and of enormous periods of time, containing multiple cycles or eras. By contrast, the unstable Western system, in which the numbers of souls continually multiplied, suggested not a continuity or equilibrium, but a beginning and an inevitable end to history, as the numbers of souls overtopped some cosmic limit.

The Eastern equilibrium system made history a timeless pool on which events spread in widening ripples, in all directions. The unstable Western system made for a history that was a rushing stream, flowing in a particular direction, from a definite beginning to a definite end.

Contained in this also was a moral account of the progress of the soul. Since the soul was immortal, it could be rewarded or punished in some future state, in ways that mortal bodies could not. In the Eastern tradition, the deeds performed in one life had consequences in the next, that maintained the equilibrium of the system of life. Thus good acts performed in one life would be rewarded in some future life, and evil acts would be punished. In this system, it remained possible for evil acts performed in one life to be redressed in subsequent lives. In the Western tradition, however, each soul had one life to live, and , at the end of time would be judged according to its conduct in that one life alone, being consigned to Hell if the judgment went against it, or to Heaven if the verdict went in its favour.

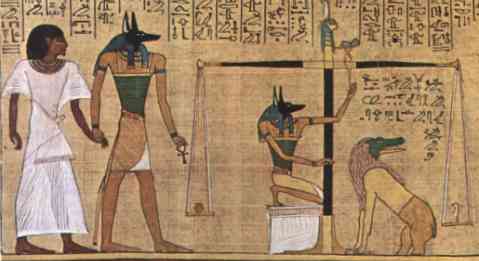

|

| The Egyptian Judgment. Hunefer's heart (conscience) on the lefthand scale is weighed against a feather on the righthand scale. Since the pivot point of the scales has been moved to the right, clearly his heart is lighter than a feather, and he will not be consumed by the crocodile-headed monster standing by the scales. |

This made for a peculiar intensity in Western society, a powerful awareness of sin and its consequences. The Eastern sinner could always make good his misdeeds in a future incarnation, but the Western sinner was saddled with them forever (but for the introduction of confession and foregiveness). For Western society, life was lived now or never. In Eastern society, it could always wait for another slow turn of the wheel of rebirth.

In both East and West, the body was seen as corrupt (and corrupting). During his life, a soul was entombed in some body, and subjected to the torment of bodily passions - of hunger, thirst, lust, and so on -. There was a tendency in the West to wish for a death which would release the soul from its tormenting carcass of flesh, and to rise up freely into the angelic realms. In the East, since death only brought rebirth, there was instead a longing for release from the wheel of Samsara, the endless cycle of rebirth.

Particularly in the Western account, where the number of souls exceeded the number of bodies available to inhabit, it naturally followed that there was a community of disembodied souls. These disembodied spirits became shades, phantoms, ghosts, demons, angels. A man might become possessed by one or more of these spirits, which might struggle for ownership of scarce bodies. Life in this vast and ever-growing community of spirits was real eternal life, and the brief interval of human life, where body and soul were united, was merely the vestibule of that eternal spiritual life. The supernatural spiritual world became more important than mundane human existence. The corruptible body was held to be a kind of dispensable garment worn by the incorruptible immortal soul. It was made of inferior material, of gross matter rather than pure spirit. The theologians and priests, whose province was that supernatural world, dealt in sacred matters. Lesser mortals - artisans, mechanics, traders, farmers - dealt in the profane world of corrupt matter. Human society became divided into sacred and secular.

This social division made for two societies. On the one hand a clergy whose central concern was the eternal spiritual life to come, and on the other hand a laity whose tasks were here-and-now mundane. The clergy gradually came to know less and less about the workings of this transient mundane world (in which it had little interest), and the laity to know less and less about the vast supernatural systems over which clerical theologians pored (and in which they had little interest either). Little by little, the sacred and the secular became entirely separate societies, living apart, speaking different languages, concerned with different matters.

The Emerging New Science of Life and Death

The foregoing account of the understanding of life and death in antiquity is intended to demonstrate the rationality and coherence of those archaic views, and their consequences for human perspectives of history. Once death came to be explained as the departure or absence of a vivifying soul, a whole stream of logical consequences could be inferred, and were inferred. But the differences between the Egyptian and Christian accounts, and between the Eastern and Western worlds, demonstrate that this was a matter of continuing enquiry and debate, not a matter of rigid dogma.

The concept of Soul was part of the science of antiquity, much as the concept of Energy is part of modern science. Human science - the attempt to understand life and the universe - did not begin with Copernicus and Galileo. All that had happened, with the arrival of modern science, was that one explanation had given way to another. The old explanation had seemed (and actually was), in its heyday, perfectly adequate.

The enquiry, as it has since continued in Western secular society, has increasingly focussed upon the nature of the human body. The dissection of bodies, and the study of their organs, led to an understanding of the human body as a machine, fueled by food and water and air, which, at death, ceased functioning. Human bodies were like automobiles, and their life could be prolonged by making repairs and replacements, even fitting new hearts or kidneys. Given massive and rapid assistance, people who would have once been regarded as dead could be brought back to life. Or they could be sustained alive indefinitely on life-support systems. Old age was simply the human equivalent of mechanical wear and tear, of subframe rust.

This mechanistic account of human life may not deny the existence of vital spirit or soul, but it renders it surplus - exactly as the inertial motion of bodies rendered a Prime Mover redundant. Western society has undergone, as a result, a slow loss of Soul.

This loss of soul brings with it the collapse of the entire system of beliefs associated with the idea of soul which were developed in antiquity. Secular Westerners do not see themselves as having immortal souls which face retribution or reward on a future Day of Judgment or in a future incarnation. For them, their lives are seen as lasting from birth to death, and no further beyond. What pleasure and delight is to be had from life must be crushed into that short interval, before death brings annihilation. The ethical consequence is that modern men have little interest in the future, except to the extent that they themselves are likely to personally experience that future. They take a short-term view, and act on a short-term basis.

But the process of transition from one understanding to another is still in process, still incomplete.

The more that men are understood to be mechanistically interchangeable - made of the same materials, fashioned into the same organs - the more their unique individual identity is eroded. Each individual man then becomes about as uniquely individual as a particular car or corn flakes packet off a production line. They become much more the same than they are different, much more alike than they are unalike. Such a loss of identity would not mean that men all thought alike and acted alike, but would mean that each would consider himself to be first and foremost human life, and only secondarily a particular case of human life.

The ethical consequence of this would be that each man would see himself as one with all men: past, present, and future. Just as his own life is made up of many distinct days, so each life would appear as a day in the life of humanity. No-one would try to cram as much experience into their life as they would try to cram as much experience into any one day in their life. Then men would as cheerfully and readily abandon their lives in service of future life, just as they would cheerfully and readily forego the a day in their own life for the sake of some future personal reward.

Or again, just as the human body is made up of millions of cells, each of which is an autonomous living organism with its birth, lifetime, and death, so each man is a part of the body of all humanity, and of all life. No man is an island, entire in himself.

Such a loss of ego, of concern with self, might seem unlikely in a world where, it seems, everyone strives mightily to assert their own unique identity. But this modern self-assertiveness may simply be the consequence of an erosion of identity that is already in process, a growing sense that we are all becoming the same, and that this sameness will make for a grim world where any one person or place is interchangeable with any another. The processes that erode identity, and which trigger attempts to restore unique identity, are many. Ours is a time when global humanity, after a long diaspora, has begun to discover what it shares in common (the same hopes, the same fears, the same planet) where once it saw only differences in colour, language, religion. It is also a time when our genetic understanding of ourselves is showing us how alike we are, despite superficial appearances. It is also a time when a global culture is emerging, extending across national borders. It is also a time when individuals may be born in one country, live in another, and die in yet another.

All racialism, nationalism, and sectarianism may then be seen as attempts to maintain (and perhaps even to create) unique identity in the face of a rising tide of homogeneity in which all differences become increasingly blurred. This attempt to retain a unique sense of identity may anyway simply be a hangover from the time when men understood themselves to possess the unique personal immortal souls.