Stripping away the Unnecessary

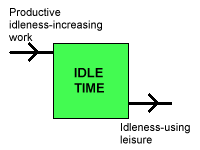

A primary economy generates idle time, and a secondary economy disposes of idle time. One creates, and the other destroys. And so the two economies can be regarded as pulling in opposite directions. What one is building up, the other is knocking down. Idle time can be regarded as much like a tank of water, into which idle time flows from the primary economy, and out of which idle time flows into the secondary economy.

A primary economy generates idle time, and a secondary economy disposes of idle time. One creates, and the other destroys. And so the two economies can be regarded as pulling in opposite directions. What one is building up, the other is knocking down. Idle time can be regarded as much like a tank of water, into which idle time flows from the primary economy, and out of which idle time flows into the secondary economy.

The two economies can interfere with one another. In a 40% idle system, 40% of time is available for idle activities. If people slack, and take more than 40% of the time as idle time, the primary economy will begin to stall, and produce less idle time. Conversely, if people overwork in the primary economy, this extra work is taken out of their idle time. The two economies work in harmony when they don't grab more time than is necessary or available. This sort of disharmony will always result in reduced idleness. The two economies may work against each other, trying to steal time from each other.

Another sort of disharmony arises where people do not see the value of their work, and try to turn work into leisure. Or when those who employ them do not see the value of leisure, and turn leisure into work. If either work or leisure is denigrated or devalued, disharmony results. And such disharmony - things working against each other, rather than with each other - reduces the efficiency of the system.

When perfect harmony is achieved, there are no inefficiencies, nothing fighting with anything else. In reality, perfect harmony is never achieved. In the most harmonious systems, most likely slightly more work is done than is strictly necessary - much like when building a house, slightly more bricks are bought than are needed, because some will be broken or lost.

Living things almost always slightly overproduce. They are like houses whose builders buy slightly too many bricks and tiles and wood and panes of glass, and who use what is left over once the house is complete to build a small annexe. Since the house is always in need of repair, and more bricks and tiles are being bought, the annexe is always growing slightly. And so living things tend to gradually grow bigger, or reproduce themselves, because they are always slightly over-maintaining themselves rather than under-maintaining themselves.

Necessities and Luxuries

Idle Theory divides goods into two sorts. On the one hand there are useful tools, and on the other there are amusing luxuries. Useful tools increase idle time, and luxuries use up idle time. Both kinds of goods cost some amount of time to produce, but useful tools give back more time than was needed to make them.

For example, if someone hunts deer to kill and eat, and one deer will keep somebody alive for 40 days, but on average it takes 30 days to catch one, then, assuming that nothing else is needed for survival, 30 days out of 40 will be spent hunting, and the hunter will be 25% idle. If the hunter now makes a bow and some arrows with which to hunt deer, and it only takes 10 days to kill a deer, then his idleness will rise to 75%. The value of the bow is that it saves 20 days of hunting.

But if someone enjoys a largely idle life, and spends much of their time hunting deer with bow and arrow, but doesn't eat their venison or make their skin into leather, then hunting is an idle pastime, and the bow and arrow is a luxury - because this second sort of hunting does not increase idleness. Instead, it is just a way of disposing of idle time.

If someone does not know whether some activity is idleness-producing work or an idleness-consuming pastime, then stopping doing it will soon demonstrate which it is. For if the hunter who lives by killing and eating deer stops making bows and arrows, then his idleness will fall from 75% to 25%. But if someone who is 25% idle, and who spends half their time hunting (but not eating) deer, and so is busy 75% of the time, were to give up hunting, they would find that their idleness increased from 25% to 75%, because they would have stripped away an entirely unnecessary pastime.

The same would be true of a bird that spends a good deal of its time preening its feathers. If this preening is done out of vanity, then it would increase its idleness if it stopped preening itself. If the preening adjusted ruffled or damaged feathers so that the bird could better fly about its business of catching insects, then if it stopped preening itself it might very well end up busier as a consequence.

Idleness is maximised by doing what is necessary and not doing what is unnecessary. Necessary work generates idle time, and unnecessary work wastes idle time. And so both humans and animals strip out unnecessary work, and only do what is necessary. And the right balance is probably achieved by continually testing variant strategies, and adopting those which result in the highest idleness.

For living things cannot afford to burden themselves with unnecessary work. If animals or humans persist in activities which have become wasteful of time rather than productive of time, they will become less and less idle as they waste more and more of their time in unproductive efforts, which could very often result in their death in the midst of plenty.

And so it must be a general rule that living things should not engage in unnecessary or unproductive activities. And since, in human life, luxuries and amusements and pastimes are unnecessary and unproductive, the application of this general rule will result in the suppression of luxury.

Puritanism

The result, in human life, of stripping away unnecessary activity is likely to be a rigorous puritanism, in which all unnecessary activities are proscribed, and only necessary productive work is carried out.

Such puritans may be regarded as purists who desire only idle time, and absolutely nothing else. Idlers who enjoy nothing so much as to have the idle time in which to sit and think, or gaze upon the world around them, and who have no great interest in material wealth, are also puritans.

And when such puritans universalise their values, and impose their values upon others by making them into law, they very often end up banning 'unnecessary' and unproductive activities like drinking and smoking and dancing. These are idle time activities that people enjoy doing. And so in practice such puritanism forbids pleasure. Puritans eschew every self-indulgent pleasure, and become 'killjoys'.

Puritans of this sort fail to distinguish between busy and idle time activities, and regard every activity as a form of work, from which the unnecessary must be stripped away. But while it makes sense that people should strip away unnecessary activities from their work, so as to expedite its progress, it makes no sense at all to strip away unnecessary activities from idle time so as to expedite its progress, because all idle time activities are always inherently unnecessary. In truth, while work should be expedited by stripping away the unnecessary, idle time activities should if anything be prolonged by making them more leisurely.

Another kind of puritan is also someone who sees life as all work, and who accordingly demands that people "keep busy" all the time. All idle time activities are seen as varieties of slacking. For puritans of this sort, sitting in pubs drinking and smoking and talking is indistinguishable from daydreaming or slacking at work. This kind of puritan believes that unproductive and self-indulgent activities like drinking and smoking would better be replaced by 'productive' work of one sort, making something useful.

Another kind of puritanism is one in which idle time is deferred indefinitely into the remote future. One day people will be able to enjoy lives of leisure, but not now. Such puritans become those sorts of industrious and inventive businessmen who make fortunes, but never enjoy their fortune. Or they become those kinds of religious enthusiasts who call upon people to work to "build the kingdom of God", and look forward to a "time of times" in the remote future.

In some ways, the problem here is that the primary imperative of maximising idle time is acting to override and nullify a secondary wish to enjoy idle time to the full. Puritanism is a consequence of taking a one-eyed view of life, and seeing only one side of it - that of maximising idle time -, and entirely forgetting that idle time thus produced is something to be enjoyed.

But maximising idle time, and then forbidding this idle time from being used pleasurably, entirely defeats the point of having idle time. It is like piping fresh water to a house, but then forbidding anyone from using it, because these various uses result in precious water being 'wasted' in cooking and cleaning.

Or it is a matter of applying primary values to secondary concerns.

The problem would not arise if working time and idle time were kept separate and distinct.

The dilemma grows from two value systems which can easily come into conflict. On the one hand there is the primary value system that seeks to accumulate idle time. And on the other hand there is a secondary value system which sets out to dispose of accumulated idle time in the most pleasant way. One sets out to distill the purest water, and the other blend the water with fruit or alcohol to make a drink, and so makes pure water impure.

Such a clash of opposing values is unlikely in the least idle societies, in which there is little idle time, and the demands of pleasure are never very great. Busy societies, necessarily almost entirely devoid of luxuries, are likely to be puritan societies, in which the appearance of toys and amusements are likely to be seen as dangerous lures to attract men from their duties, and which could utterly ruin a society. In busy societies, the imperatives of work and accumulation must always outweigh the allures of idle luxuries, if society is to not disintegrate.

But in the idlest of societies, the opposite is likely to be true. For in the idlest of societies, almost all time will be idle time, and all activities play, and luxuries will be abundant. And at the same time, it will have become almost impossible to increase idleness further, and so invention will have ceased. In these circumstances, the lure of luxury and pleasure will greatly outweigh the demands of time-productive work.

It is probably in societies in which idle time and necessary work are of approximately equal scale that a clash of values is likely to be the most intense, particularly if it is one half of society which performs the work, and the other half which enjoys the leisure.

Striking the Right Balance

The opposite of puritanism might be an extreme of hedonistic dissipation, in which every imaginable pleasure is indulged.

Puritanism and hedonism might be seen as destructive extremes. At some level of idleness, this idleness defines how much work must be done, and how many hours of idle pleasure may be enjoyed. A 40% idle individual will spend 40% of his time diligently working, and 60% of his time engaged in idle pleasures.

But a nominally 40% idle puritan might spend all his time working, and a nominally 40% idle hedonist might spend none of his time working.

The hedonist would not survive long. With work left undone, he would soon find himself short of food and clothing and shelter, and he would suffer the pain of hunger and cold before he finally died.

The overworking puritan would survive, but his life would be a pain of self-imposed work no less arduous than the suffering of the hedonist. He would not suffer the physical pains of hunger and cold, but he would live under the lash of his own unbending instruction.

The hedonist, once his profligacy had resulted in physical suffering, would live a short and unpleasant life. But the puritan would live a long and unpleasant life. Which kind of life is to be preferred?

The right balance is found when an individual works no more than he has to work, and enjoys idle pastimes no longer than his idle hours permit. And someone who finds this balance will live just as long as any self-denying puritan, but also enjoy that life to the fullest extent permitted.

For if the purpose of work is produce not things of one sort or other, but to produce idle time, then it is futile if such idle time is not enjoyed to the full. Harm only comes if somone puritanically overworks, or hedonistically underworks.

In busy societies, this balance will always be found living a busy, industrious life with few moments of idle pleasure. And in idle societies, the same balance will be found in many hours of idle pleasure, interspersed with a brief periods of diligent work.